Thursday, December 9, 2021 7:30 p.m.

PERFORMERS

Hannah Penn, mezzo-soprano

Katherine Goforth, tenor

Nicholas Meyer, baritone

Sequoia, piano

Lisa Lipton, clarinet

Amelia Lukas, flute/piccolo

DURATION

90 mins. Including intermission

PROGRAM

GEORGE BUTTERWORTH Loveliest of Trees

GEORGE BUTTERWORTH Look Not in My Eyes

WILLIAM DENNIS BROWNE To Gratiana, Dancing and Singing

RALPH VAUGHAN-WILLIAMS Youth and Love

GEORGE BUTTERWORTH When I was One and Twenty

IVOR GURNEY If Death to Either Shall Come

GEORGE BUTTERWORTH Think, No More, Lad

CHARLES IVES He is There

CHARLES IVES Tom Sails Away

POWELL / WILLIAMS & JUDGE Pack Up Your Troubles / It’s a Long Way to Tipperary*

INTERMISSION – 15 minutes

AL PIANTADOSI I Didn’t Raise My Boy to be a Soldier*

GEORGE M. COHAN Over There*

Letter by Captain A. E. McKennett, Engineer Railway

CHARLES IVES In Flanders Fields

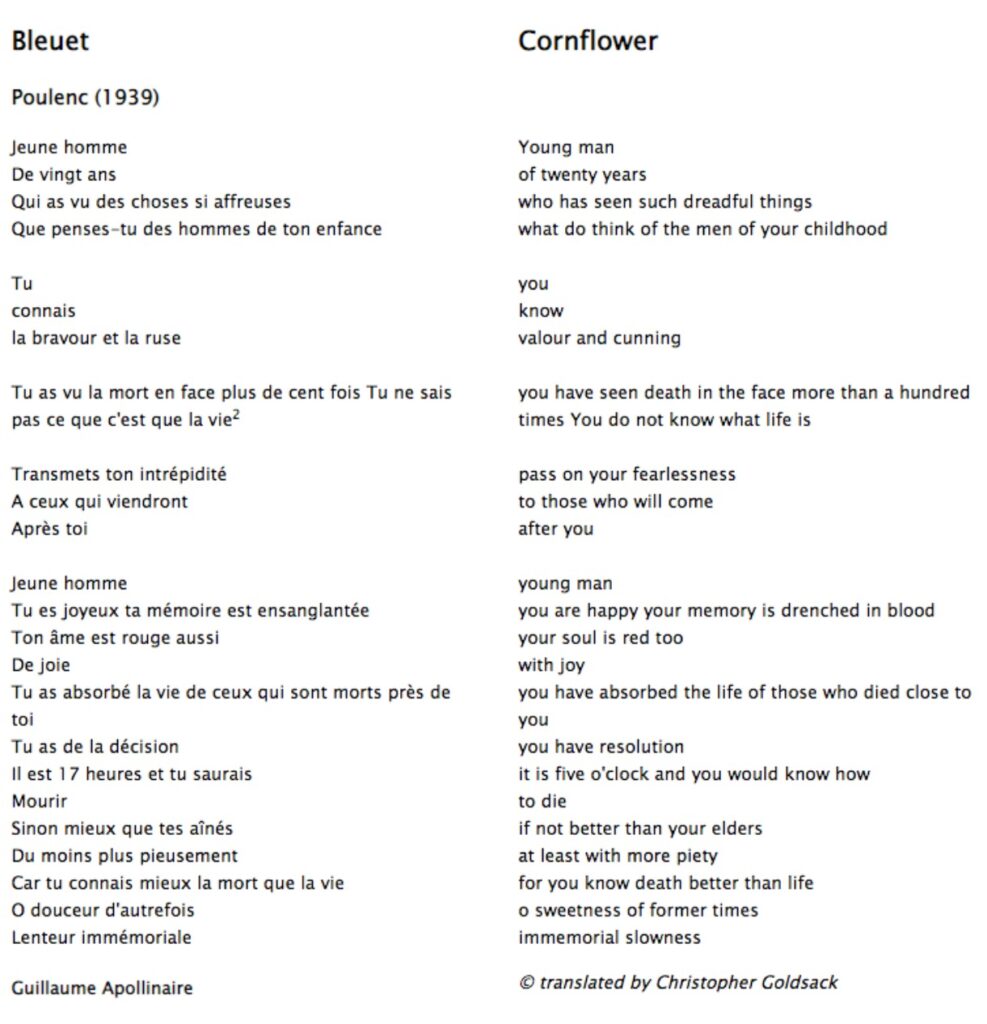

FRANCIS POULENC Bleuet

IVOR GURNEY Sleep

RUDI STEPHAN Kythere

GEORGE BUTTERWORTH The Lads in Their Hundreds

ANONYMOUS TRENCH SONG Hanging On The Old Barbed Wire

RALPH VAUGHAN-WILLIAMS Silent Noon

GEORGE BUTTERWORTH Is My Team Ploughing

*popular songs arranged by Justin Ralls

TRANSLATIONS:

ABOUT THE COSTUMES

Nicholas Meyer is wearing an Italian officer’s jacket from ca. 1915-1930. Lisa Lipton is wearing a bugler’s jacket that was worn by a young American soldier who shipped out from New York in 1917. Amelia Lukas and Lisa Lipton are wearing jewelry from the 1910s, and Amelia Lukas is wearing a reproduction of a suffragette’s sash from the early 1900s. Hannah Penn is wearing a reproduction of the uniform of a World War I nurse, Sequoia’s costume has been inspired by pictures of Charles Ives, and Katherine Goforth’s costume is inspired by a picture of an Italian World War I soldier recovering at US Red Cross Hospital #7 at Jouy-sur-Morin, France.

ABOUT THE COMPOSERS

George Butterworth (1885-1916)

When George Butterworth began studying Classics at Trinity College in 1904, his father expected him to become a lawyer. Instead, he spent his time in school developing his skills as a musician, composer, and a collector of traditional English folk song and dance. During this time, Butterworth made friends with fellow folk art collectors Francis Jekyll, Cecil Sharp, and Ralph Vaughan Williams. It took Butterworth time to make a name for himself as a composer, but in the years before World War I, he wrote most of his surviving works, including Two English Idylls, The Banks of Green Willow, and the symphonic poem A Shropshire Lad. In 1914, he first enlisted as a private, and then received a commission as a Lieutenant and fought on the Western Front, where he received the Military Cross for bravery and leadership. On the morning of August 5, 1916, Butterworth was leading his battalion in digging a trench during the Battle of the Somme. He was shot and killed, and his body was never recovered. For his leadership on the day of his death, he was recommended for a second Military Cross.

William Denis Browne (1888-1915)

At the outbreak of World War I, the British war poet Rupert Brooke was awarded a commission in the British Royal Navy by Winston Churchill. He agreed to accept it, on the condition that his childhood friend, William Denis Browne, also be awarded a commission. Browne was an unusual musician: a piano student of Ferruccio Busoni who had experience as a conductor, recitalist, composer, and music teacher. But he struggled to build a career, because he worked in so many different fields. Brooke died of malaria before they saw combat, and shortly afterward, Browne was shot by a sniper. He was then wounded twice more during the Third Battle of Krithia, and his unit was forced to retreat without him.

During the retreat, Browne gave his wallet to a comrade. Inside was a handwritten message: “I’ve gone now too; not too badly I hope. I’m luckier than Rupert, because I’ve fought. But there’s no one to bury me as I buried him, so perhaps he’s best off in the long run… Good-bye, my dear, & bless you always for your goodness to me. W.D.B.” On the day before he died, Browne wrote a letter to Edward Dent, the executor of his will, stating, “It’s all rubbish except Gratiana, (perhaps) Salathiel Pavey, & the Comic Spirit… Everything else except what I’ve mentioned must be destroyed.” Following these instructions, Dent assessed Browne’s scores with Ralph Vaughan Williams and the tenor Steuart Wilson, and burned each score that did not “represent Denis Browne at his best.”

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

Ralph Vaughan Williams was 42 years old and an established composer when WWI began. Although he could have avoided military service due to his age, or used his influence to receive a post that was well out of any danger, he enlisted as a private in the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1914. Vaughan Williams and other medical orderlies were required to work on the battlefield at all hours, often under heavy fire. A colleague described a typical night: “Slowly we worked our way along the trenches, our only guide our feet, forcing ourselves through the black wall of night and helped occasionally by the flash of the torch in front. Soon our arms begin to grow tired, the whole weight is thrown onto the slings, which begin to bite into our shoulders; our shoulders sag forward, the sling finds its way into the back of our necks; we feel half suffocated, and with a gasp at one another the stretcher is slowly lowered to the duckboards. A twelve-stone man rolled up in several blankets on a stretcher is no mean load to carry when every step has to be carefully chosen and is merely a shuffle forward of a few inches only.”

In 1917, Vaughan Williams was called to military duty in the Royal Garrison Artillery. Working with heavy artillery caused irreparable damage to his hearing, and it is believed that the constant sound of gunfire caused his deafness later in life.

Ivor Gurney (1890-1937)

Ivor Gurney was studying at the Royal College of Music when WWI began, and he left school to enlist as a private in the Gloucestershire Regiment in February 1915. Although Gurney saw himself as a composer first, he started to write poetry while he served on the Western Front, including his most famous volume, entitled Severn and Somme. It was also on the front that he was first shot in the shoulder in April 1917, and then was a victim of a chemical gas attack five months later. Gurney stoically described the experience in a letter to his friend Marion Scott: “Being gassed (mildly) with the new gas is no worse than catarrh or a bad cold.” Gurney was sent to Edinburgh War Hospital, where he fell in love with Annie Nelson Drummond, a nurse, and where he had a serious mental breakdown when their relationship ended.

Gurney’s mental health continued to decline after he was discharged from the army. He dropped out of the Royal College of Music and was committed to the City of London Mental Hospital in 1922, where his visitors included his former teacher Ralph Vaughan Williams. His time there was marked by the delusion that he was William Shakespeare, and he even wrote plays in Shakespearean verse. He died in the same hospital in 1937, of tuberculosis. Gurney is memorialized with sixteen others, including Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, in the war poets’ memorial at Westminster Abbey.

George M. Cohan (1878-1942)

As part of their family group “The Four Cohans,” George M. Cohan learned to sing, dance, and most importantly, to write on vaudeville stages in the late 1800s. His career on the stages of New York is legendary, not only as the composer of “You’re A Grand Old Flag,” “Give My Regards To Broadway,” and “Yankee Doodle,” but, as the New York Times wrote in his obituary, as “… the first man in the American theatre. Songwriter, dancer, actor, playwright, producer, theatre owner–he was the most versatile person in show business.”

The lyrics of “Over There,” written in 1917, were meant to inspire Americans to join the war effort. The song sold 1.5 million copies, in addition to the recordings that were made by vaudeville superstar Nora Bayes, opera superstar Enrico Caruso, and the Peerless Quartet (who also recorded “I Didn’t Raise My Boy To Be A Soldier”). Joseph Tumulty, secretary to President Woodrow Wilson, wrote this message to thank Cohan: “Dear George Cohan: The President considers your war song ‘Over There’ a genuine inspiration to all American manhood.”

Later in life, Cohan became the only composer to be awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, presented by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to honor his contributions to morale during World War I. He delayed his reception of the award by a year, due to his opposition to President Roosevelt’s politics.

Charles Ives (1874-1954)

The music of Charles Ives is unusual, enigmatic, contradictory, and hard to describe, like the composer himself. He was a virtuoso organist from childhood, mentored by his musician father at home and taught composition by Horatio Parker at Yale, who also spent his professional life selling insurance.

Even though Ives disagreed with US intervention in a foreign war, he fervently supported the US war machine, serving on a war bond committee chaired by Franklin Delano Roosevelt. It is said that Ives had his first heart attack in response to an argument with Roosevelt about issuing $50 war bonds (Roosevelt allegedly dismissed the idea of a $50 war bond as “useless”, which infuriated Ives).

Ives’ Three War Songs were composed as responses to World War I and depict Ives’ conflicted feelings about it. These pieces feature classic style features of Ives’ music like extended piano technique, bitonal or atonal harmony and the quotation of Civil War, folk and popular tunes.

”Pack Up Your Troubles”

“Pack Up Your Troubles” was composed by two brothers, George Henry Powell (1880-1951), alias “George Asaf,” and Felix Powell (1878-1942) a British songwriting team who performed in music halls. Felix initially presented the melody during a writing session, where it was quickly discarded into a drawer marked “Duds.” But then came a World War I competition to write the “best morale-building song.” “Pack Up Your Troubles” won first prize. Felix is reported as saying, “A few months [after submitting “Pack Up Your Troubles”] a wire came up to us at the Grand Theatre, Birmingham: PACK UP YOUR TROUBLES FIRST PRIZE… On the following Monday we put the song into our own show at Southampton in order to ‘try it on the dog’ so to speak. By the middle of the week we were as amused as we were delighted to hear thousands of troops singing it en route for the docks.”

This marked a departure point for the Powell brothers. While George was a committed pacifist and conscientious objector to the war, Felix became a Staff Sergeant in the British Army. During the course of the war, he watched countless men die in the trenches while hearing them singing the song that he had written. Aubrey Powell, the grandson of Felix, said, “It meant he was earning huge amounts of money back home while other men were dying at the front. He was singing and encouraging them to fight with this song, and I think it got to him. By all accounts he had a kind of nervous breakdown in the trenches. He found it unbearable.” When the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, Felix heard British soldiers singing “Pack Up Your Troubles” as they prepared to march home. Then he heard the song echoing across no man’s land and sung in German. During the war, “Pack Up Your Troubles” had become an international hit.

After returning home, Felix struggled to compose, presumably consumed by battlefield memories. The brothers moved to East Sussex where they ran a newspaper and eventually opened a theatre. In the 1940s, Felix was desperate to repeat his success as a composer and set to work writing a new musical, but the show fell apart in rehearsals. Having accepted enormous loans to produce the show and with no way to pay them back, he dressed in his military uniform, wrote a note that said, “I can’t write anymore,” and ended his own life. Due to the outbreak of World War II, “Pack Up Your Troubles” became popular again. Felix’s widow received his royalty checks and used them to pay off his debts.

”It’s A Long Way To Tipperary”

Jack Judge (1872-1938) told a famous story about the composition of “It’s A Long, Long Way To Tipperary”: One night at midnight, he bet that he could compose a great song by morning, and on the way home heard someone say, “It’s a long way to…” inspiring the song. The story is not exactly true. Judge did produce a song the next morning, but it was merely an adaptation of a song called “It’s A Long Way To Connemara” that he had written in 1909 with Harry Williams (1873-1924).

The song first gained notoriety as part of Judge’s music hall show, but took off when George Curnock, a journalist working for the Daily Mail, heard a regiment singing the song as they marched into France. The Mail printed the complete lyrics of the song as part of the story, and within a few months, the famous Irish tenor John McCormack had recorded the song and it was selling 10,000 copies per day.

”I Didn’t Raise My Boy To Be A Soldier”

American opinion was divided on the topic of participating in World War I. Many groups, including Protestant Christians, German-Americans, pacifists, and political isolationists were opposed to war on philosophical or moral grounds. They were the intended audience of what has been called the first anti-war or protest song in American history.

The song was written by a Tin Pan Alley writing team of lyricist Alfred Bryan and composer Al Piantadosi. It was recorded in December 1914 (at the same time as McCormack recorded “Tipperary”) and sold 650,000 copies in 1915. Dedicated to “mothers everywhere,” “I Didn’t Raise My Boy” also represented a feminist viewpoint in the context of its time. Voices and Visions, an online companion to US and World History courses maintained by the University of Wisconsin, relates, “In their struggle to expand the right to vote to all women, suffragists used many strategies. One of them was to argue for the moral superiority of women, largely because their presence in the domestic sphere insulated them from corrupting influences… The mother of the song clearly defines herself by her relationship to her son, who the song describes as “all she cared to call her own.” Based on the authority that she derives from such a selfless calling as motherhood, she demands that society recognize that her son belongs to her and not be sent to war.”

The song had many critics, including former President Theodore Roosevelt, who suggested an alternate title, “I Didn’t Raise My Girl to Be a Mother,” while future President Harry S Truman stated said that women who were anti war belonged “in China—or by preference in a harem—and not in the United States.” Parodies of the song ranged from serious efforts by war supporters like “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier, But I’ll Send My Girl to Be a Nurse,” to parodies like “I Didn’t Raise My Dog to Be a Sausage.”

Bryan and Piantadosi were not ideological pacifists, but professional songwriters who wanted to write a hit. In 1917 (concurrent with “Over There”), Bryan wrote the pro-war song, “Joan Of Arc, They Are Calling You.”

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) and Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918)

Francis Poulenc’s three years of compulsory service in the French Army began in January 1918. He served for several months on the Western Front but was later assigned to perform clerical work for the Ministry of Aviation, where he composed in his spare time. The song “Bleuet” was not composed until 1939, at the outbreak of World War II, and has been viewed as a reflection on the war-to-come. The text, which describes a young soldier “of 20 years of age,” was written by the poet Guillaume Apollinaire in 1918 after he had suffered a shrapnel injury to his head while fighting in the infantry on the Western Front.

Poulenc and Apollinaire were not close friends, but they did know each other. Poulenc had set Apollinaire’s writing to music during World War I, most famously in his opera Les mamelles de Tirésias, which Apollinaire saw after receiving his injury. There was no chance for this relationship to deepen, because Apollinaire, who had not recovered from his injuries, died of influenza in 1918 only days before the Armistice was signed. Poulenc went on to set Apollinaire’s words many times, including in Quatre poèmes de Guillaume Apollinaire (1931), La grenouillère (1938), three sets called Deux poèmes d’Apollinaire (1939, 1941-45, 1946), Banalités (1940), and Calligrammes (1948).

Rudi Stephan (1887-1915)

In the years before World War I, Rudi Stephan was a rising star in the world of German classical music. In 1912, he had great success with a composition entitled simply, Musik für Orchester, and he had just completed his first opera, Die ersten Menschen (“The First People”), when he was called up to active duty on the Eastern Front. He was shot and killed two days after he arrived. Today, Stephan is remembered as the most famous German composer to be killed in World War I. Die ersten Menschen was posthumously premiered in 1920, and the Gymnasium (prep school) he had attended in his home of Worms renamed itself Rudi-Stephan-Gymnasium, but his works were neglected after his death. In 1945, the Allies bombed Worms, and most of Stephan’s manuscripts and works-in-progress were destroyed.

Program Notes by Katherine Goforth